Working with blend modes is almost always an experimental process. Because it’s nearly impossible to predict the results, you always seem to end up experimenting with different modes and Fill Opacities until you get the results you’re looking for.

In this article I’m going to give you a high-level view of what the various blend modes do, and then I’ll dig deeper into the nuts and bolts of the blend modes by explaining some of the math involved, and their interrelationships with each other. I’m not going to “show” you how the blend modes work—I’m going to “explain” how they work. By the time you finish reading this article, you should have a better idea of how to use blend modes and where to begin your “experimentation,” which in turn should reduce the time it takes to achieve the results you’re looking for.

In this article I’m going to give you a high-level view of what the various blend modes do, and then I’ll dig deeper into the nuts and bolts of the blend modes by explaining some of the math involved, and their interrelationships with each other. I’m not going to “show” you how the blend modes work—I’m going to “explain” how they work. By the time you finish reading this article, you should have a better idea of how to use blend modes and where to begin your “experimentation,” which in turn should reduce the time it takes to achieve the results you’re looking for.

How Blend Modes Work

The Opacity slider in the Layers Panel allows you to blend the active layer with the layers below by making the active layer translucent, which in turn allow the layers below to show through. The blend modes found in Photoshop allow the same process to take place, but by using different mathematical calculations for each blend mode. As of Photoshop CS5, there are 27 blend modes—2 new blend modes, Subtract and Divide, where recently added. Any changes made using blend modes are parametric, i.e., the changes are non-destructive, and you can always revisit your blend mode settings and readjust them as needed without damaging the pixels in your original image.

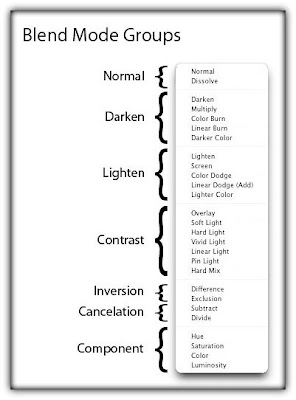

Blend Mode Groups

While the blend mode names don’t make all that much sense, Adobe did group the blend modes into logical groups.

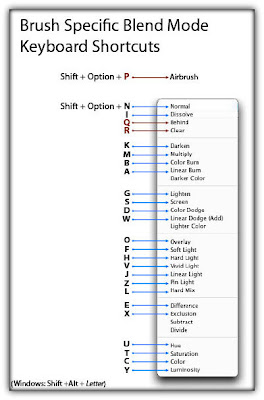

The majority of blend modes have keyboard shortcuts. To use these shortcuts, your current tool must be something other than one of the tools found in the painting and editing section of the Tools Panel (where the Brush Tool, Healing Brush, Stamp, Eraser, etc. are found—see the illustration below). This is because the tools in the painting and editing section have blend mode settings of their own, and if you have one of these tools selected, their blend mode options will take precedence over the blend mode options found in the Layers Panel. For example, if you use Shift+Option+M to switch to the Multiply blend mode while you have the Paint tool selected, the Paint tool’s blend mode will be changed to Multiply, not the blend mode option in the Layers Panel. The good news is that these same blend mode shortcuts DO work for the painting tools, you just need to pay attention to what tool you have selected when you use the shortcuts.

The Painting and Editing section of the Tools Panel

It’s also possible to scroll up or down the blend mode list by using the keyboard combinations Shift+ (scrolls down the blend mode list), or Shift- (scrolls up the blend mode list). These keyboard shortcuts also work differently depending on what tool you have selected in the Tools Panel. For example, if you have the Paint tool selected and you use Shift+, the blend mode for the Paint tool will scroll down to the next blend mode in the list (not the blend mode in the Layers Panel).

There are also keyboard shortcuts for changing the Standard Opacity and Fill Opacity settings in the Layers Panel. To use these shortcuts, your current tool must be something other than one of the tools found in the painting and editing section of the Tools Panel. To change the Standard Opacity using the keyboard, just hit a number. For example, you can change the opacity to 50% by hitting the 5 key, or change the opacity to 100% by hitting the 0 key. You can even hit 44 for 44% opacity. The only opacity setting you can’t set using a keyboard shortcut, is setting the opacity to 0%. For that, you’ll have to use your mouse to adjust the slider or type the value in the dialog box.

Adjusting the Fill Opacity works using the same technique, but you need to use the Shift key when hitting a number. For example, to set the Fill Opacity to 33%, use the keyboard combination Shift+33. These keyboard shortcuts also work when one of the tools in the painting and editing section of the Tools Panel is selected, however once again, the blend mode settings for these tools take precedence over the blend mode settings in the Layers Panel. For example, if you have the Paint tool selected and you use the keyboard combination 22, the opacity for the Paint tool will be changed to 22%. One thing to note is that there isn’t a Fill Opacity setting for the any of the tools in the painting and editing section, however, some of the tools do have a Flow setting (the Brush Tool for example). For those tools that have a Flow setting, using Shift+number will change the Flow for the selected tool. For example, if you use Shift+22 with the Paint tool selected, the Flow for the Paint tool will be set to 22%.

It’s also possible to scroll up or down the blend mode list by using the keyboard combinations Shift+ (scrolls down the blend mode list), or Shift- (scrolls up the blend mode list). These keyboard shortcuts also work differently depending on what tool you have selected in the Tools Panel. For example, if you have the Paint tool selected and you use Shift+, the blend mode for the Paint tool will scroll down to the next blend mode in the list (not the blend mode in the Layers Panel).

There are also keyboard shortcuts for changing the Standard Opacity and Fill Opacity settings in the Layers Panel. To use these shortcuts, your current tool must be something other than one of the tools found in the painting and editing section of the Tools Panel. To change the Standard Opacity using the keyboard, just hit a number. For example, you can change the opacity to 50% by hitting the 5 key, or change the opacity to 100% by hitting the 0 key. You can even hit 44 for 44% opacity. The only opacity setting you can’t set using a keyboard shortcut, is setting the opacity to 0%. For that, you’ll have to use your mouse to adjust the slider or type the value in the dialog box.

Adjusting the Fill Opacity works using the same technique, but you need to use the Shift key when hitting a number. For example, to set the Fill Opacity to 33%, use the keyboard combination Shift+33. These keyboard shortcuts also work when one of the tools in the painting and editing section of the Tools Panel is selected, however once again, the blend mode settings for these tools take precedence over the blend mode settings in the Layers Panel. For example, if you have the Paint tool selected and you use the keyboard combination 22, the opacity for the Paint tool will be changed to 22%. One thing to note is that there isn’t a Fill Opacity setting for the any of the tools in the painting and editing section, however, some of the tools do have a Flow setting (the Brush Tool for example). For those tools that have a Flow setting, using Shift+number will change the Flow for the selected tool. For example, if you use Shift+22 with the Paint tool selected, the Flow for the Paint tool will be set to 22%.

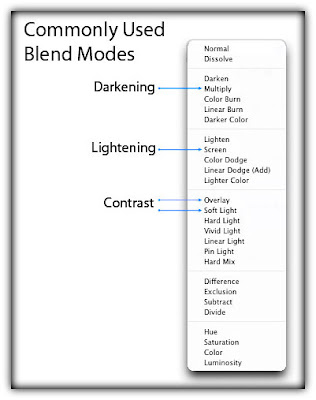

Some of the more commonly used blend modes are Multiply, Screen, Overlay and Soft Light.

Commonly Used Blend Modes

Blend Mode Opposites

Each of the blend modes in the Darken group have an opposite (complementary) mode in the Lighten group. These “opposites” use slightly different math to arrive at their results, but the logic they use is similar but reversed. For example, with the Darken blend mode, if the pixels on the active layer are darker than the ones on the layers below, they are kept in the image. The opposite blend mode to Darken is Lighten, and with the Lighten blend mode, if the pixels on the active layer are lighter than the ones on the layers below, they are kept in the image.

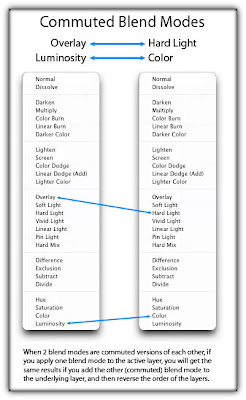

There are 2 pairs of blend modes that are commuted versions of each other. The first commuted pair is the Overlay and Hard Light modes. The second pair is the Luminosity and Color modes. When 2 blend modes are commuted versions of each other, if you apply one blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same results if you add the other (commuted) blend mode to the underlying layer, and then reverse the order of the layers.

Commuted Blend Modes

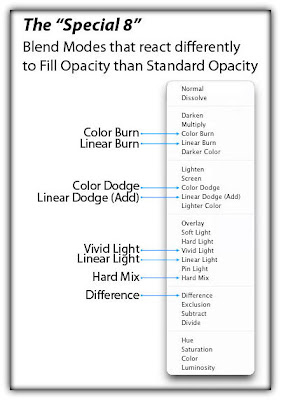

The “Special 8” Blend Modes

There are 8 blend modes that I’ll be referring to as the “Special 8.” These blend modes behave differently when Fill Opacity is adjusted, compared to when standard Opacity is adjusted. The blend modes that aren’t members of this Special 8 group react the same to both Fill and Opacity changes (assuming there are no Layer Effects), but with these Special 8 blend modes, 40% Opacity will look different than 40% Fill, or 30% Opacity will look different than 30% Fill, etc. For all of the other blend modes (the modes that aren’t part of the Special 8), 40% Opacity looks the same as 40% Fill, or 20% Opacity looks the same as 20% Fill, etc. This is an important concept to understand, because it can extend the capabilities of these blend modes. For example, the Hard Mix blend mode usually doesn’t look all that great, but when you adjust the Fill Opacity for this mode, you can get some great results. The blend modes that are members of this Special 8 group are Color Burn, Linear Burn, Color Dodge, Linear Dodge (Add), Vivid Light, Linear Light, Hard Mix, and Difference.

Blend Mode Math

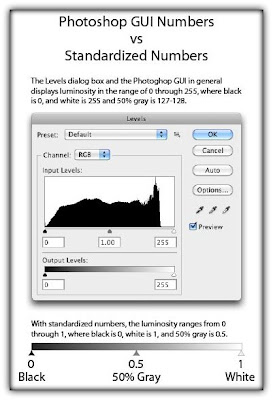

Before I list the 27 blend modes and how they work, you need to understand how the math in Photoshop works. Because the blend modes work with brightness and darkness values, i.e., luminance levels, and because luminance levels appear as values from 0 to 255 in Photoshop (as seen with the Levels dialog box), you would assume that the math Photoshop performs is based on these values. However, in the background, Photoshop “standardizes” these luminance values before applying the math. When these values are standardized, white (255) becomes 1, black (0) remains at 0, and 50% gray becomes 0.5. All of the blend mode math takes place in the small range between 0 and 1. It’s important that you understand this concept of standardization, so you can understand the following mathematical equations.

Standardized Numbers

Blend Mode Math

Before I list the 27 blend modes and how they work, you need to understand how the math in Photoshop works. Because the blend modes work with brightness and darkness values, i.e., luminance levels, and because luminance levels appear as values from 0 to 255 in Photoshop (as seen with the Levels dialog box), you would assume that the math Photoshop performs is based on these values. However, in the background, Photoshop “standardizes” these luminance values before applying the math. When these values are standardized, white (255) becomes 1, black (0) remains at 0, and 50% gray becomes 0.5. All of the blend mode math takes place in the small range between 0 and 1. It’s important that you understand this concept of standardization, so you can understand the following mathematical equations.

Standardized Numbers

Because the luminance values are standardized before the math is applied, and the math is working with numbers ranging between 0 and 1, the resulting calculations may not be what you would expect. For example, when working with numbers greater than 1, division results in a smaller number, and multiplication results in a larger number. However, when working with numbers between 0 and 1, division results in a larger number, and multiplication results in a smaller number. Subtraction and addition work pretty much as you would expect, weather you’re working with numbers greater than 1, or values between 0 and 1.

Below are some examples using arbitrary numbers that show how the math results differ when working with numbers between 0 and 1 versus numbers between 0 and 255. To help you better understand the numeric values illustrated below, the regular luminance number 200 is converted to a standardized number by using: 200 ÷ 255 = 0.78, and the regular number 72 is converted to a standardized number by using: 72 ÷ 255 = 0.28.

Divide Example

Background layer ÷ Active layer = Quotient

Regular Luminance Numbers:

200 ÷ 72 = 2.78

A darkening effect

Standardized Luminance Numbers:

0.78 ÷ 0.28 = 2.78

A brightening effect where whites are blown-out

BLEND MODE DESCRIPTION

NORMAL GROUP

Dissolve

The Dissolve blend mode on acts on transparent and partially transparent pixels – it treats transparency as a pixel pattern and applies a diffusion dither pattern.

DARKEN GROUP

Darken

If the pixels of the selected layer are darker then the ones on the layers below, they are kept in the image. If the pixels in the layer are lighter, they are replaced with the tones on the layers below (they show through to the selected layer), so basically the darker tones of all layers are kept. Note that this behavior is on a channel by channel basis, i.e., this rule is applied to each of the 3 RGB color channels separately. If you want to apply the same Darken blend mode behavior on a composite basis, use the Darker Color blend mode instead (however this typically results in harsher transitions).

Multiply

The best mode for darkening. Works by multiplying the luminance levels of the current layer’s pixels with the pixels in the layers below. Great for creating shadows and removing whites and other light colors (while keeping the darker colors). As an analogy, think of the selected layer and all of the layers below as individual transparencies, and that they are stacked on top of each other, and then placed on an overhead projector. Using this analogy, the light passing through the lighter areas will have trouble getting through the darker areas, but the lighter areas will shine through other lighter areas with relative ease. If the Multiply blend mode isn’t dark enough for what you’re working on, try the Linear Burn or Color Burn modes. Math: A×B (Active Layer multiplied by Background Layer).

Color Burn (Special 8)

Darker than Multiply, with more highly saturated mid-tones and reduced highlights. This is one of the “Special 8” that I mentioned earlier, where Fill and Opacity behave differently. Math: 1−(1−B)÷A (Background Layer inverted, divided by Active Layer, and the quotient is then inverted).

Linear Burn (Special 8)

Darker than Multiply, but less saturated than Color Burn. This is one of the “Special 8” that I mentioned earlier, where Fill and Opacity behave differently. Math: A+B−1 (Active Layer plus Background Layer, then white is subtracted from the sum (an inversion).

Darker Color

Similar to the Darken blend mode, but darkens on the composite channel, instead of separate RGB color channels.

LIGHTEN GROUP

Lighten

If the pixels of the selected layer are lighter then the ones on the layers below, they are kept in the image (the opposite of the Darken blend mode). If the pixels in the layer are darker, they are replaced with the pixels on the layers below (they show through to the selected layer). Note that this behavior is on a channel by channel basis, i.e., this rule is applied to each of the 3 RGB color channels separately. If you want to apply the same Lighten blend mode behavior on a composite basis, use the Lighter Color blend mode instead (however this typically results in harsher transitions).

Screen

Similar to the Lighten blend mode, but brighter and removes more of the dark pixels, and results in smoother transitions. Works somewhat like the Multiply blend mode, in that it multiplies the light pixels (instead of the dark pixels like the Multiply blend mode does). As an analogy, imagine the selected layer and each of the underlying layers as being 35mm slides, and each slide being placed in a separate projector (one slide for each projector), then all of the projectors are turned on and pointed at the same projector screen…this is the effect of the Screen blend mode. This is a great mode for making blacks disappear while keeping the whites, and for making glow effects. Math: 1−(1−A)×(1−B) (A inverted multiplied by B inverted, and the product is inverted).

Color Dodge (Special 8)

Brighter than the Screen blend mode. Results in an intense, contrasty color-typically results in saturated mid-tones and blown highlights. Math: B÷(1−A) (B divided by A inverted).

Linear Dodge (Add) (Special 8)

Brighter than the Color Dodge blend mode, but less saturated and intense. This mode “Adds” the luminance levels. Math: A+B (A plus B).

Lighter Color

Similar to the Lighten blend mode, but lightens on the composite channel, instead of separate color channels. Compares each pixel and gives you the lighter of the two (and usually results in harsher transitions).

CONTRAST GROUP

All of the Contrast modes work by lightening the lightest pixels, darkening the darkest pixels, and dropping the gray mid-tones (50% gray). This is achieved by using combinations of the lightening and darkening modes from the Lighten and Darken groups. The Contrast blend modes work by checking if the colors are either darker than medium gray, or lighter than medium gray. If they are darker then medium gray, then a darkening blend mode is applied. Conversely, if the colors are brighter then medium gray, then a brightening mode is applied. The mid-point (50% gray), is dropped. For each of the Contrast blend modes, the math is applied against complementary (opposite) blend modes. For example, the Overlay blend mode uses a combination of the Multiply and Screen Blend modes, and these modes are complements of each other. The other complementary blend modes are: Darken/Lighten, Color Burn/Color Dodge, Linear Burn/Linear Dodge (Add), Darker Color /Lighter Color.

Overlay

Uses a combination of the Screen blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Multiply blend mode on the darker pixels. It uses a half-strength application of these modes, and the mid-tones (50% gray) becomes transparent. One difference between the Overlay blend mode and the other Contrast blend modes, is that it makes its calculations based on the brightness of the layers below the active layer—all of the other Contrast modes make their calculations based on the brightness of the active layer. To get results similar to the Overlay mode, but where the blend mode favors the active layer, use the Hard Light blend mode (it uses the same math, but favors the active layer). Another thing to note about the Overlay blend mode, is that it and the Hard Light blend mode are commuted versions of each other. This means that if you apply the Overlay blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same effect if you apply the Hard Light blend mode to the layer below, and then switch the order of the layers.

Soft Light

Uses a combination of the Screen blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Multiply blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). Similar to the Overlay blend mode, but results in a more organic effect that is softer—results in somewhat transparent highlights and shadows.

Hard Light

Uses a combination of the Linear Dodge blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Linear Burn blend mode on the darker pixels. It uses a half-strength application of these modes, and uses the same math as the Overlay blend mode, but favors the active layer, as opposed to the underlying layers. The effect is more intense than the Overlay blend mode, and results in harsher light. Another thing to note about the Hard Light blend mode, is that it and the Overlay blend mode are commuted versions of each other. This means that if you apply the Hard Light blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same effect if you apply the Overlay blend mode to the layer below, and then switch the order of the layers.

Vivid Light (Special 8)

Uses a combination of the Color Dodge Mode on the lighter pixels, and the Color Burn blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). Similar to the Hard Mix blend mode in overdrive, and typically results in a more extreme effect.

Linear Light (Special 8)

Uses a combination of the Linear Dodge blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Linear Burn blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). Similar to the Vivid Light blend mode in overdrive, and typically results in a more extreme effect.

Pin Light

Uses a combination of the Lighten blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Darken blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). If the dark pixels on the active layer are darker than the dark pixels on the underlying layers, they will be visible, if they aren’t, they drop away. If the pixels on the active layer are lighter than the pixels on the underlying layers, they will also be visible, if they aren’t, they drop away. This is a wild blend mode that can result in patches or blotches (large noise), and it completely removes all mid-tones.

Hard Mix (Special 8)

Uses the Linear Light blend mode set to a threshold, so for each RGB color channel, pixels in each channel are converted to either all black or all white. Once the math is applied to each separate channel, and the composite channel is created, the resulting composite can contain up to 8 colors: Red, Green, Blue, Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black and White. Note that this mode is a member of the “Special 8″ blend modes, and it reacts differently to Fill Opacity than it does to Standard Opacity. If you reduce the Fill Opacity when using this mode, the number of colors in the image will increase beyond the previously mentioned 8 colors. This can be considered another one of the extreme blends modes, but adjusting the Fill Opacity, the effect can be tempered and great results can be attained.

INVERSION GROUP

Difference (Special 8)

Subtracts a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the composite view of the underlying layers (B-A), and results in only absolute numbers (the subtraction never produces a negative number—if it turns out to be a negative number, it’s converted into a positive number). It does a selective inversion where black never gets inverted, white inverts absolutely, and all of the other luminance levels invert based on their brightness on a channel-by-channel basis. With this blend mode, similar colors cancel each other, and the resulting color is black.

Exclusion

Subtracts a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the composite view of the underlying layers (B-A), and results in only absolute numbers (the subtraction never produces a negative number). It does a selective inversion where black never gets inverted, white inverts absolutely, and all of the other luminance levels invert based on their brightness on a channel-by-channel basis. With this blend mode, similar colors cancel each other, and the resulting color is gray. This mode is basically the same as the Difference blend mode, except when similar colors cancel each other, the resulting color is gray instead of black.

CANCELLATION GROUP

Subtract

Subtracts a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the composite view of the underlying layers (B-A). Similar to the Difference mode, but doesn’t convert the whites to an absolute number. Blacks don’t change any colors (because black = 0, and AnyColor – 0 = AnyColor), and whites drop out to blacks (because whites are such a large number, and all of the other numbers will be less than whites, so the resulting color will always be black). With this blend mode, similar colors cancel each other, and the resulting color is black. Math: B−A (B minus A).

Divide

Divides a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the underlying layers on a channel by channel basis (B÷A). This mode typically results in extreme highlights because dividing the “standardized” luminance numbers results in a larger number. Whites don’t change any colors (because white = 1, and AnyColor÷1 = AnyColor). Similar colors turn white (because AnyColor÷Anycolor = 1), with the exception of blacks, which stay black (because 0÷0 = 0). Math: B÷A (B divided by A).

COMPONENT GROUP

Hue

Keeps the Hue of the active layer, and blends the luminance and saturation of the underlying layers (you basically get the image from the lower layer with the colors of the top layer).

Saturation

Keeps the saturation of the active layer, and blends the luminosity and hue from the underlying layers—where colors from the active layer are saturated, they will appear using the luminosity and hue from the underlying layers.

Background layer ÷ Active layer = Quotient

Regular Luminance Numbers:

200 ÷ 72 = 2.78

A darkening effect

Standardized Luminance Numbers:

0.78 ÷ 0.28 = 2.78

A brightening effect where whites are blown-out

BLEND MODE DESCRIPTION

NORMAL GROUP

Dissolve

The Dissolve blend mode on acts on transparent and partially transparent pixels – it treats transparency as a pixel pattern and applies a diffusion dither pattern.

DARKEN GROUP

Darken

If the pixels of the selected layer are darker then the ones on the layers below, they are kept in the image. If the pixels in the layer are lighter, they are replaced with the tones on the layers below (they show through to the selected layer), so basically the darker tones of all layers are kept. Note that this behavior is on a channel by channel basis, i.e., this rule is applied to each of the 3 RGB color channels separately. If you want to apply the same Darken blend mode behavior on a composite basis, use the Darker Color blend mode instead (however this typically results in harsher transitions).

Multiply

The best mode for darkening. Works by multiplying the luminance levels of the current layer’s pixels with the pixels in the layers below. Great for creating shadows and removing whites and other light colors (while keeping the darker colors). As an analogy, think of the selected layer and all of the layers below as individual transparencies, and that they are stacked on top of each other, and then placed on an overhead projector. Using this analogy, the light passing through the lighter areas will have trouble getting through the darker areas, but the lighter areas will shine through other lighter areas with relative ease. If the Multiply blend mode isn’t dark enough for what you’re working on, try the Linear Burn or Color Burn modes. Math: A×B (Active Layer multiplied by Background Layer).

Color Burn (Special 8)

Darker than Multiply, with more highly saturated mid-tones and reduced highlights. This is one of the “Special 8” that I mentioned earlier, where Fill and Opacity behave differently. Math: 1−(1−B)÷A (Background Layer inverted, divided by Active Layer, and the quotient is then inverted).

Linear Burn (Special 8)

Darker than Multiply, but less saturated than Color Burn. This is one of the “Special 8” that I mentioned earlier, where Fill and Opacity behave differently. Math: A+B−1 (Active Layer plus Background Layer, then white is subtracted from the sum (an inversion).

Darker Color

Similar to the Darken blend mode, but darkens on the composite channel, instead of separate RGB color channels.

LIGHTEN GROUP

Lighten

If the pixels of the selected layer are lighter then the ones on the layers below, they are kept in the image (the opposite of the Darken blend mode). If the pixels in the layer are darker, they are replaced with the pixels on the layers below (they show through to the selected layer). Note that this behavior is on a channel by channel basis, i.e., this rule is applied to each of the 3 RGB color channels separately. If you want to apply the same Lighten blend mode behavior on a composite basis, use the Lighter Color blend mode instead (however this typically results in harsher transitions).

Screen

Similar to the Lighten blend mode, but brighter and removes more of the dark pixels, and results in smoother transitions. Works somewhat like the Multiply blend mode, in that it multiplies the light pixels (instead of the dark pixels like the Multiply blend mode does). As an analogy, imagine the selected layer and each of the underlying layers as being 35mm slides, and each slide being placed in a separate projector (one slide for each projector), then all of the projectors are turned on and pointed at the same projector screen…this is the effect of the Screen blend mode. This is a great mode for making blacks disappear while keeping the whites, and for making glow effects. Math: 1−(1−A)×(1−B) (A inverted multiplied by B inverted, and the product is inverted).

Color Dodge (Special 8)

Brighter than the Screen blend mode. Results in an intense, contrasty color-typically results in saturated mid-tones and blown highlights. Math: B÷(1−A) (B divided by A inverted).

Linear Dodge (Add) (Special 8)

Brighter than the Color Dodge blend mode, but less saturated and intense. This mode “Adds” the luminance levels. Math: A+B (A plus B).

Lighter Color

Similar to the Lighten blend mode, but lightens on the composite channel, instead of separate color channels. Compares each pixel and gives you the lighter of the two (and usually results in harsher transitions).

CONTRAST GROUP

All of the Contrast modes work by lightening the lightest pixels, darkening the darkest pixels, and dropping the gray mid-tones (50% gray). This is achieved by using combinations of the lightening and darkening modes from the Lighten and Darken groups. The Contrast blend modes work by checking if the colors are either darker than medium gray, or lighter than medium gray. If they are darker then medium gray, then a darkening blend mode is applied. Conversely, if the colors are brighter then medium gray, then a brightening mode is applied. The mid-point (50% gray), is dropped. For each of the Contrast blend modes, the math is applied against complementary (opposite) blend modes. For example, the Overlay blend mode uses a combination of the Multiply and Screen Blend modes, and these modes are complements of each other. The other complementary blend modes are: Darken/Lighten, Color Burn/Color Dodge, Linear Burn/Linear Dodge (Add), Darker Color /Lighter Color.

Overlay

Uses a combination of the Screen blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Multiply blend mode on the darker pixels. It uses a half-strength application of these modes, and the mid-tones (50% gray) becomes transparent. One difference between the Overlay blend mode and the other Contrast blend modes, is that it makes its calculations based on the brightness of the layers below the active layer—all of the other Contrast modes make their calculations based on the brightness of the active layer. To get results similar to the Overlay mode, but where the blend mode favors the active layer, use the Hard Light blend mode (it uses the same math, but favors the active layer). Another thing to note about the Overlay blend mode, is that it and the Hard Light blend mode are commuted versions of each other. This means that if you apply the Overlay blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same effect if you apply the Hard Light blend mode to the layer below, and then switch the order of the layers.

Soft Light

Uses a combination of the Screen blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Multiply blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). Similar to the Overlay blend mode, but results in a more organic effect that is softer—results in somewhat transparent highlights and shadows.

Hard Light

Uses a combination of the Linear Dodge blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Linear Burn blend mode on the darker pixels. It uses a half-strength application of these modes, and uses the same math as the Overlay blend mode, but favors the active layer, as opposed to the underlying layers. The effect is more intense than the Overlay blend mode, and results in harsher light. Another thing to note about the Hard Light blend mode, is that it and the Overlay blend mode are commuted versions of each other. This means that if you apply the Hard Light blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same effect if you apply the Overlay blend mode to the layer below, and then switch the order of the layers.

Vivid Light (Special 8)

Uses a combination of the Color Dodge Mode on the lighter pixels, and the Color Burn blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). Similar to the Hard Mix blend mode in overdrive, and typically results in a more extreme effect.

Linear Light (Special 8)

Uses a combination of the Linear Dodge blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Linear Burn blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). Similar to the Vivid Light blend mode in overdrive, and typically results in a more extreme effect.

Pin Light

Uses a combination of the Lighten blend mode on the lighter pixels, and the Darken blend mode on the darker pixels (a half-strength application of both modes). If the dark pixels on the active layer are darker than the dark pixels on the underlying layers, they will be visible, if they aren’t, they drop away. If the pixels on the active layer are lighter than the pixels on the underlying layers, they will also be visible, if they aren’t, they drop away. This is a wild blend mode that can result in patches or blotches (large noise), and it completely removes all mid-tones.

Hard Mix (Special 8)

Uses the Linear Light blend mode set to a threshold, so for each RGB color channel, pixels in each channel are converted to either all black or all white. Once the math is applied to each separate channel, and the composite channel is created, the resulting composite can contain up to 8 colors: Red, Green, Blue, Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black and White. Note that this mode is a member of the “Special 8″ blend modes, and it reacts differently to Fill Opacity than it does to Standard Opacity. If you reduce the Fill Opacity when using this mode, the number of colors in the image will increase beyond the previously mentioned 8 colors. This can be considered another one of the extreme blends modes, but adjusting the Fill Opacity, the effect can be tempered and great results can be attained.

INVERSION GROUP

Difference (Special 8)

Subtracts a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the composite view of the underlying layers (B-A), and results in only absolute numbers (the subtraction never produces a negative number—if it turns out to be a negative number, it’s converted into a positive number). It does a selective inversion where black never gets inverted, white inverts absolutely, and all of the other luminance levels invert based on their brightness on a channel-by-channel basis. With this blend mode, similar colors cancel each other, and the resulting color is black.

Exclusion

Subtracts a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the composite view of the underlying layers (B-A), and results in only absolute numbers (the subtraction never produces a negative number). It does a selective inversion where black never gets inverted, white inverts absolutely, and all of the other luminance levels invert based on their brightness on a channel-by-channel basis. With this blend mode, similar colors cancel each other, and the resulting color is gray. This mode is basically the same as the Difference blend mode, except when similar colors cancel each other, the resulting color is gray instead of black.

CANCELLATION GROUP

Subtract

Subtracts a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the composite view of the underlying layers (B-A). Similar to the Difference mode, but doesn’t convert the whites to an absolute number. Blacks don’t change any colors (because black = 0, and AnyColor – 0 = AnyColor), and whites drop out to blacks (because whites are such a large number, and all of the other numbers will be less than whites, so the resulting color will always be black). With this blend mode, similar colors cancel each other, and the resulting color is black. Math: B−A (B minus A).

Divide

Divides a pixel on the active layer, from an equivalent pixel in the underlying layers on a channel by channel basis (B÷A). This mode typically results in extreme highlights because dividing the “standardized” luminance numbers results in a larger number. Whites don’t change any colors (because white = 1, and AnyColor÷1 = AnyColor). Similar colors turn white (because AnyColor÷Anycolor = 1), with the exception of blacks, which stay black (because 0÷0 = 0). Math: B÷A (B divided by A).

COMPONENT GROUP

Hue

Keeps the Hue of the active layer, and blends the luminance and saturation of the underlying layers (you basically get the image from the lower layer with the colors of the top layer).

Saturation

Keeps the saturation of the active layer, and blends the luminosity and hue from the underlying layers—where colors from the active layer are saturated, they will appear using the luminosity and hue from the underlying layers.

Color

Keeps the color of the active layer, and blends the hue and saturation (the color) of the active layer with the luminance of the lower layers (a handy way to change the color of an image). Another thing to note about the Color blend mode, is that it and the Luminosity blend mode are commuted versions of each other. This means that if you apply the Color blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same effect if you apply the Luminosity blend mode to the layer below, and then switch the order of the layers.

Luminosity

Keeps the luminance of the active layer, and blends it with hue and saturation (the color) of the composite view of the layers below. This results in the colors of the underlying layers being blended with the active layer, and replacing them. Another thing to note about the Luminosity blend mode, is that it and the Color blend mode are commuted versions of each other. This means that if you apply the Color blend mode to the active layer, you will get the same effect if you apply the Luminosity blend mode to the layer below, and then switch the order of the layers.

Brush Tool-Specific Keyboard Shortcuts

The Brush Tool has some additional blend modes and associated keyboard shortcuts. These blend modes, which aren’t found in the Layer panel’s blend mode list, are “Behind” and “Clear.” There is also an Airbrush option that, while it’s not really a blend mode, it does have a keyboard shortcut that’s worth mentioning. The behind blend mode will apply paint only on transparent pixels in a layer, and will leave the opaque pixels intact. The Clear blend mode basically turns your brush into an eraser by making the pixels you paint on transparent.

Pass Through Mode

The default blend mode for a layer group is “Pass Through.” The Pass Through mode tells Photoshop to act as if there isn’t a group—it’s like temporarily taking the layers out of the group to perform the blending in the usual order. If Pass Through is changed to a different mode, you’re basically changing the order in which the layers are processed—all layers within the group are blended first, and then the resulting composite is blended with the layers below using the blend mode selected for the group (the layers within the group are acted on first).

Article By Robert Thomas

What i was searching, i got it.

ReplyDeleteGr8. Keep Learning & Sharing Knowledge...! Goodluck...!

Delete